What Is the Duodenum?

The duodenum is one small but important part of the digestive system, the complex series of organs and processes that turn food into energy. In addition to the liver, pancreas, and gallbladder, the digestive system is comprised of the gastrointestinal tract; this group of long, hollow organs is responsible for breaking down food into useful nutrients and eliminating waste from the body. The digestive tract runs in sequence from the mouth and esophagus to the stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and anus. The duodenum is located near the middle of this long chain at the first part of the small intestine and directly after the stomach.

What Does the Duodenum Do?

The purpose of the upper gastrointestinal tract is to gradually break down food into smaller and smaller components. Once food has entered the stomach, the process of peristalsis reduces the contents to a mostly liquid substance called chyme. The pyloric sphincter, located at the base of the stomach, slowly and selectively releases some of this chyme so that the only particles that go through are small enough to enter the small intestine. The chyme then exits directly from the pyloric sphincter into the duodenum.

The duodenum is a roughly C-shaped section of the small intestine that is connected to the other non-GI tract organs of the digestive system via small tubes. Bile, produced by the liver and stored in the gallbladder, is introduced to the digestive tract at the duodenum along with enzymes from the pancreas. In an overall sense, the duodenum is like a staging area where the chyme is prepared for the next phase of digestion. Once the digestive juices enter through the duodenum, the chyme is further broken down into individual molecules that can eventually be absorbed as it travels through the jejunum and ileum.

Another element in the preparation of chyme for digestion involves the secretion of certain hormones. Cholecystokinin is one of the hormones released by the duodenum; cholecystokinin is a peptide hormone that is specifically helpful in the digestion of fats and proteins. It also acts as a hunger suppressant. Secretin is one of the other hormones released in the duodenum. Secretin is also a peptide hormone, but it regulates electrolytes and the pH balance of the chyme that passes through the small intestine.

Structure of the Duodenum

At around 10 inches long, the duodenum is the smallest section of the small intestine. The curved C-shape actually wraps around the pancreas where it receives important pancreatic enzymes and bile from the liver. The duodenum itself is divided into four segments that each have a different purpose:

- Superior part: The section of the duodenum that is closest to the stomach is known as the superior part or the duodenal bulb. The duodenal bulb is connected to the liver via the hepatoduodenal ligament, a structure that houses the hepatic artery, portal vein, and common bile duct. The duodenal bulb ends at the superior duodenal flexure, where the duodenum turns down toward the descending part.

- Descending part: The second part of the duodenum extends downwards and marks the point where the digestive tract exits the peritoneum (lining of the abdominal cavity). This section is also the site where the common biliary duct and pancreatic duct join to form a new duct called the ampulla of Vater. The descending part terminates at the inferior duodenal flexure.

- Horizontal part: The third section is called the horizontal part and runs laterally from the abdominal aorta to the inferior vena cava. It also sits directly behind the superior mesenteric artery.

- Ascending part: The fourth and final section of the duodenum is called the ascending part because it turns upward toward the transition to the jejunum at the duodenojejunal flexure. The ascending part is also attached to the abdominal wall through a structure called the ligament of Treitz; this marks the dividing point between the upper and lower gastrointestinal tracts.

Like many internal organs, the walls of the duodenum are composed of several different layers of tissue. These layers are essentially identical to all other sections of the gastrointestinal tract in terms of composition, and they all perform similar functions. Below are the four main layers, in order of innermost to outermost:

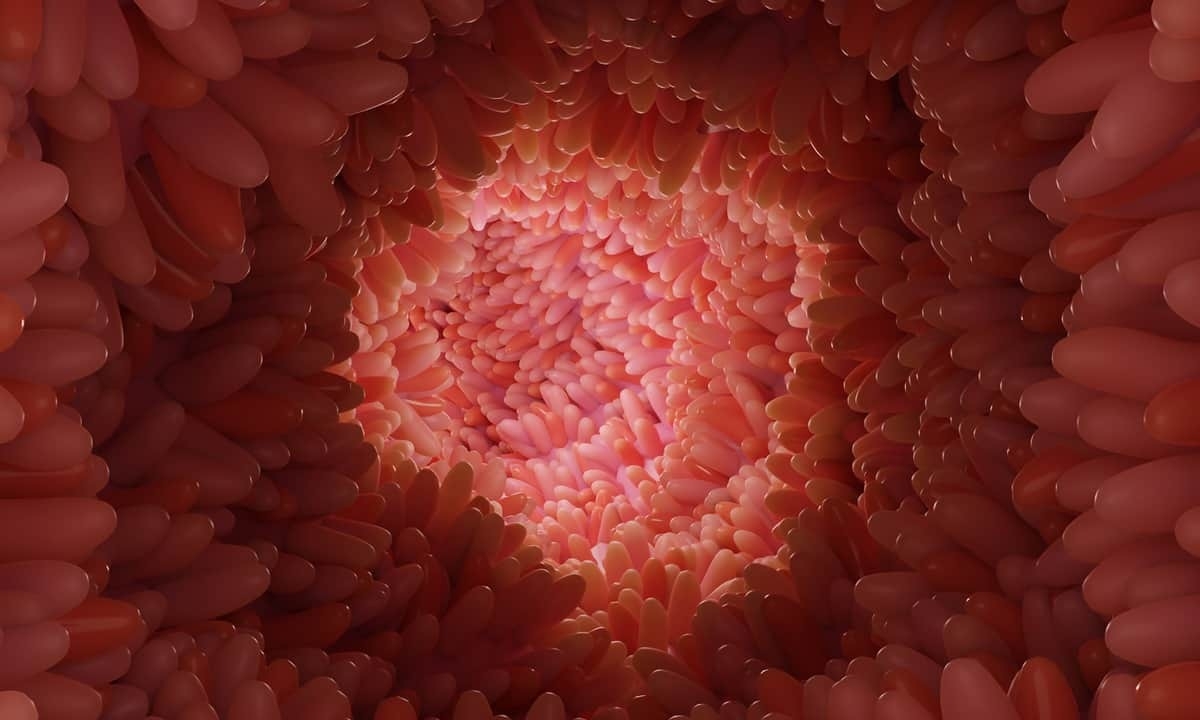

- Mucosa: The mucosal layer is the innermost layer of the small intestine, and it includes mucous glands and microvilli; microvilli are tiny, fingerlike structures that project out from the intestinal walls in order to help with the absorption of nutrients.

- Submucosa: The submucosal layer is mostly made up of connective tissue, blood vessels, and nerves. This layer also includes a specific type of glands called Brunner’s glands. Brunner’s glands secrete mucus for easing the passage of chyme and bicarbonate for neutralizing stomach acid that was introduced earlier in the digestive process.

- Muscularis: The muscularis externa layer is composed of smooth muscle tissue and is primarily responsible for contracting (peristalsis) in such a way as to churn the chyme and move it along through the small intestine. This churning and mixing with digestive enzymes allows nutrients in the chyme to be more easily absorbed into the bloodstream.

- Serosa: The outermost layer of the small intestine is the serosal layer, and it is mostly in place as a protective cover for the organ. The serosa is made of squamous epithelial cells, the same type of single-layer tissue that lines the outside of numerous other internal organs.

Problems in the Duodenum

Like other parts of the digestive system, the duodenum can be involved in various gastrointestinal conditions. One of the reasons for this is its location; in addition to being at roughly the midpoint of the digestive tract, the duodenum is also directly connected to the other digestive organs that aren’t part of the tract. This is why, for example, cancerous cells that are present in the liver and pancreas are often concurrently present in the duodenum. Below are some common ailments that can affect the duodenum:

- IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease can affect both the intestines and the stomach, but the only type that involves the duodenum is Crohn’s disease. With IBD, inflammation of the duodenal lining can cause symptoms like abdominal pain, diarrhea, reduced appetite, or blood in the stool.

- Celiac disease: Celiac disease mainly involves the duodenum and jejunum in the small intestine and is characterized by an intolerance to gluten, a protein found in grains.

- Duodenitis: Duodenitis is the term for specific inflammation of the duodenum that causes symptoms like abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Duodenitis can be triggered by a variety of causes, including Helicobacter pylori infections, overuse of NSAIDs, or some types of autoimmune disease.

- Ulcers: Duodenal ulcers are similar to peptic ulcers (found in the stomach) in that they represent a perforation of the inner lining of the duodenum. These lesions can be caused by some of the same stimuli that cause duodenitis and typically lead to common gastrointestinal symptoms.

Contact a Gastroenterologist

Because the digestive tract is made up of similar materials and is all connected, it’s quite common for mild health concerns to crop up. However, this also makes it difficult to specifically diagnose a problem with the duodenum just from symptoms. This is why it’s important to stay on top of your digestive health care with regular checkups and healthy eating habits. If you’ve had gastrointestinal symptoms that you can’t explain or that have not been getting better, it may be time to connect with a gastroenterologist at Cary Gastro. To learn more, please contact us today to request an appointment.